History of the National Theater

Building of the National Theater

The Cuvilliés-Theater, completed in 1755, proved to be too small for the quickly increasing Munich population. So, in 1792, the then Elector of Bavaria Karl Theodor commissioned a new opera house to be built by Court Architect Maximilian von Verschaffelt. However, the project was far too complex and time-consuming and was never completed, and so the new Elector Max IV Joseph decided to call a competition. All those who were engaged with architecture were invited to send in their ideas for the building of the century. The project particularly appealed to a young man, Karl von Fischer, who was barely twenty years old, born on the 19th of September 1782 in Mannheim. Influenced by the French Revolution’s ideals of citizen rights, he designed an open theatre, where the seats were no longer divided by rows and boxes.

The Theater in 2013. By Avda – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27425403

The Director of the Royal Theatre Josef Marius von Babo established a stock company for the building of the Nationaltheater, but plans were postponed due to the Napoleonic Wars. In 1806, the Elector Max I Joseph became King of Bavaria, and Karl von Fischer was his leading architect. The King was so impressed by a visit to the Théâtre de l’Odéon in Paris that he ordered a test be carried out to see whether the “Paris Model” could work in Munich. In March 1811, Karl von Fischer’s edited plans were approved by the King and on the 26th of October that same year Prince Ludwig set down the founding stone.

The execution proved to be as difficult as the planning. Just after a year of building work, finances were exhausted. The tough winter of 1813 and the Russian campaign led to a halt in construction. Since there were no new sponsors to win over, the King bought back the stocks and continued building at the cost of the state. Finally, on the 12th of October 1818, the theatre was opened. Having received much criticism during the construction, Karl von Fischer did not see his great project completed: he died on the 12th of February 1820, barely 40 years old.

Rebuilding 1823-1825

During a performance on the 14th of January 1823, a fire broke out on the stage set. The theatre was burnt down to its foundations. The King was inconsolable and the entire country mourned with him. In the end, the city of Munich took over the entire cost of rebuilding, which amounted to 800,000 Guilders. Under the direction of Leo von Klenze, the theatre was reconstructed within just two years, including a few small corrections. On the 2nd of January 1825, the Nationaltheater was reopened.

Destruction and Rebuilding 1943-1963

In the Second World War, the theatre was destroyed for the second time. In the night of the 3rd of October 1943, explosives and fire bombs struck the theatre. The heat was so intense that it melted the iron-framed stage. The rebuilding of the Residenztheater in 1951 had already exceeded the budget, so that the Landtag (State Parliament) opposed the rebuilding of the Nationaltheater. Not only that, but city planners wanted to remove the ruins completely to make more room for transport services in the city centre. For this reason, a citizen’s group called “Friends of the Nationaltheater” was founded in 1952, which collected additional funds and won over public support for the reconstruction of the theatre.

In 1954, a competition was established for the new building. At first, a design true to the original construction seemed out of the question. The Ministry of Culture decided to develop a draft submitted by Gerhard Graubner. Working together with the then Government Architect, Karl Fischer, they created more variations on Graubner’s design, making the possibility of reconstruction seem achievable.

In the end, the original plan by Karl von Fischer was chosen, cleared of Leo von Klenze’s additions during his reluctant reconstruction of the theatre as well as other changes of the 19th Century. The work of rebuilding lasted five years and cost 62 Million Marks. On the 21st of November, the company – which in the meantime had been housed at the Prinzregententheater – took possession of its theatre.

History of the Cuvilliés-Theater

In the 18th Century, Munich received its second opera house with the Cuvilliés-Theater, originally called the “Residenztheater”. The Elector of Bavaria, Max III Joseph, gave the commission to the Court Architect Francois Cuvilliés the Elder and, just three years later, on the 12th of October 1753, the splendid German Roccoco theater was opened with Ferrandini’s opera seria Catone in Utica. With its rotating stage and adjustable stalls, which could be set horizontally on festive occasions, the “New Opera House” was a significant technical accomplishment.

Originally, the “New Opera House at the Royal Residence” was only for courtly use; however, when the opera house at Salavtorplatz was forced to close, the Elector of Bavaria decided in 1797 to establish the Cuvilliés-Theater as a Royal and National Theatre, making German opera and theatre accessible to the people.

In 1823, the Cuvilliés-Theater was renovated as a result of damages caused by the fire which burnt down the Nationaltheater in 1817. King Ludwig I decided to shut down the theatre completely in 1831, and from 1834 onwards it was used as a warehouse for the Nationaltheater’s stage sets. As a result of Director Franz von Dingelstedt’s insistence, the theatre was finally reopened in 1857.

More recently, the theatre shut again at the beginning of 1944. In order to keep it safe from bomb attacks during the Second World War, the entire interior was removed and housed in two different locations outside the city. On the 18th March, the external walls of the bare building were destroyed during an air raid. After the war, the new Residenztheater was built on its foundations. The former Cuvilliés-Theater, which had never possessed a facade, was reconstructed in 1957/58 on the Apotheke Floor of the Residenztheater in its original Roccoco style, based on designs taken from the archives of Ecole Bavaroise de l´Architecture.

The Bayerische Staatsoper has a wonderful virtual tour of their theaters. The following gallery is just a sample of the magnificent 360 degrees images available on the tour.

GALLERY

Munich’s operatic history

Munich’s operatic history began with the courtly splendor of the young Italian “dramma per musica”, that new, initially exclusive, yet later – in Venice – universally popular form of musical theatre. Elector Ferdinand Maria installed a theatre in the Hercules Hall of the Residence, where the first Italian opera performances were staged for the members of the court society. Concurrently, following a his father Maximilian I’s plan, he also built the first free-standing opera house in Germany by taking the old grain storehouse, the so-called “Haberkasten” (“Oat Bin”), on Salvatorplatz, and reconstructing it as a baroque theatre. The courtly period operas were generally based on mythology and used allegorical figures to pay homage to the ruler and his court. Often the technical apparatus with its flying machines, sea battles and triumphal marches vied for primacy with the music.

During the reign of Elector Max II Emanuel, between 1679 and 1726, Italian opera continued its own triumphal march in Munich. His successor, Maximilian III Joseph, then commissioned François Cuvilliés to construct the “teatro nuovo presso la residenza”, the Residence Theatre – to this day the Cuvilliés-Theater is a household name for opera lovers all over the world. The “dramma per musica” had meanwhile become the “opera seria” with the featuring the cult of the aria, the bel canto style, the prima donnas and the castrati. Gradually folk operas and musical entertainments emerged from the middle class. Mythological subjects and homages to rulers began yielding to more life-like subject matter drawn from everyday life. New decisive impulses came from such sources as the French revolutionary “opéra comique” and the “singspiel” from Vienna and Leipzig.

The “opera buffa”, a combination of a vast array of different style elements, determined the style of La finta giardinera, the opera 19-year old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was commissioned to write for Munich. Six years later, on commission from Elector Karl Theodor, he composed his first “opera seria”. The world première of this work Idomeneo – re di Creta on January 29, 1781 in the Residence Theatre marked a major breakthrough for the 25-year old composer.

The artistic and political trends in the first quarter of the 19th century were determined by Max IV Joseph, who ruled from 1799 on as Elector, then, following the elevation of Bavaria to the status of kingdom, from 1806 to 1825 as King Max I. In 1802, the old “Haberkasten” on Salvatorplatz was torn down. The “Hof-National-Schaubühne” (“Court-National Theatrical Stage”) moved into the Cuvilliés Theatre becoming the “Churfürstliches Hoftheater” (“Electoral Court Theatre”). One of the last decisive acts of Bavaria’s King Max was the laying of the cornerstone for the Royal Court and National Theatre on Marstallplatz in 1811. This house, built to plans by Carl von Fischer, burned down on January 14, 1823, but thanks to the willingness of the Munich citizenry to make sacrifices, it was restored under the direction of architect Leo von Klenze and was able to reopen its doors only two years later.

With the accession of King Ludwig I, who continued his father’s tradition from 1825 to 1848, and the revival of the new National Theatre, another new epoch in Munich’s operatic history began. Measures undertaken by the king included the closing of the “Volkstheater” at the Isartor and the final dissolution of the Italian opera. This opened the way for local forces as well as for a number of new trends emanating from all over Europe.

The reign of Bavaria’s opera-enthusiast story-book King Ludwig II from 1864 to 1886 is closely tied in with the name of Richard Wagner. Shortly after his accession, the 19-year old king, who had been totally enchanted by Wagner’s Lohengrin, brought the totally debt-ridden composer to Munich. The controversial friendship between monarch and musician, which ended in a political wrangle, ushered in a new heyday for opera in Munich – indeed for opera itself. Milestones in this development included the world premières of four masterworks by Richard Wagner. On June 10, 1865 the new court conductor Hans von Bülow conducted Tristan und Isolde, and three years later Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. There followed on September 22, 1869 and June 26, 1870 the world premières of Das Rheingold and Die Walküre under the musical direction of Franz Wüllner. In 1888, Die Feen was given its world première. The Royal Court and National Theatre was in the limelight of the European musical world.

The administration of General Director Franz von Perfall, from 1867 to 1893, saw the initiation of the Opera Festival. He put on a festival summer for the first time in 1875, featuring operas by Mozart and music dramas by Wagner. Over the course of time, the festival idea began to demand its own festival playhouse – and so, under the new General Director Ernst von Possart, the Prinzregententheater was constructed one year after the turn of the 20th century, fulfilling a wish on the part of Munich’s citizens and fostered by the art-loving Prince Regent Luitpold. The grand opening on August 21, 1901 with Die Meistersinger under Hermann Zumpe was a veritable popular festival and inaugurated a magnificent era for the Munich Opera Festival.

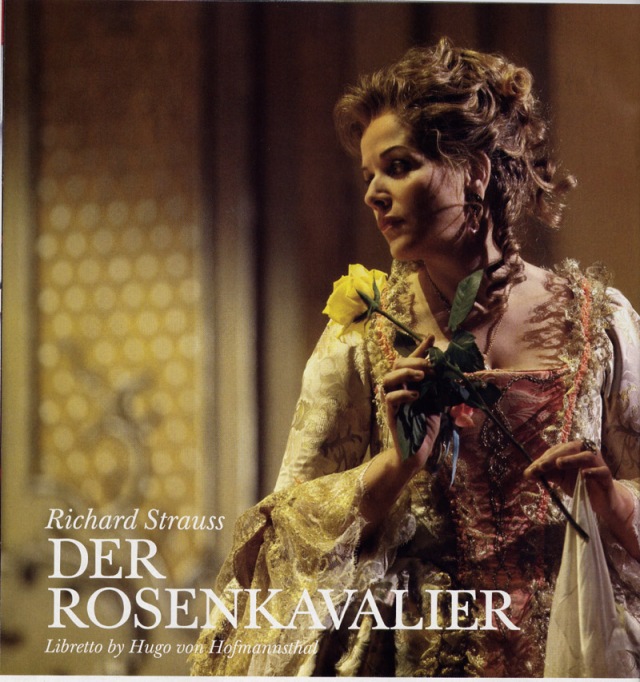

Zumpe’s successor, Felix Mottl, prepared the ground for Richard Strauss in his home town of Munich, even if audiences may initially have been shocked by the first performances of Salome, Elektra and the revival of the satirical operatic poem, Feuersnot. Mottl’s last major conducting assignment was the Munich première of the Rosenkavalier on February 1, 1911, at which point in time Richard Strauss joined Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Richard Wagner to form the harmonious triad of the Munich Opera Festival. Illustrious artists such as Enrico Caruso, Karl Erb and Maria Ivogün were making the Munich Opera world famous back then.

Bruno Walter’s premières opened up brand-new worlds of sound with the major works of Franz Schreker, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Max von Schillings and Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos. Starting in 1922, Bruno Walter’s successor Hans Knappertsbusch began a continuous 14-year period that left a no less indelible imprint on the Munich Opera. During his administration, Munich witnessed the emergence of such conductors as Robert Heger, Karl Elmendorff, Paul Schmitz, Karl Böhm and Carl Tutein. Wilhelm Furtwängler and Hans Pfitzner were on the podium for performances in the National Theatre and the Prinzregententheater. When Hans Knappertsbusch was forced out of the theatre along with Clemens von Franckenstein, both victims of political ostracism, the Munich theatre was virtually orphaned for two years. Knappertsbusch’s name, however, became the stuff legends are made of.

During the Third Reich, Munich was slated to get another opera house. With Clemens Krauss, who served in the joint capacity of general manager and general music director, Munich was able to develop even further despite oppression and war. Clemens Krauss supplied highlights both in his career and in the history of the National Theatre with the world premières of three works by his friend Richard Strauss, three fantastic anachronisms which nevertheless became artistic reality: Friedenstag in 1938, Verklungene Feste in 1941, and Capriccio in 1942. During an Allied bombardment in the night of October 3 / 4, the National Theatre was turned into an eerie ruin. Further damage and destruction as well as the proclamation of “total war” silenced the State Opera for a while.

The arduous tasks of restoring the theatre to life were assumed by General Manager Georg Hartmann and his General Music Director Georg Solti. After they had successfully introduced works by Paul Hindemith and Heinrich Sutermeister, and Werner Egk had established himself in 1948 with his Faust ballet Abraxas, Hartmann and Solti put on the first post-war Munich Opera Festival in 1950, creating on a firm foundation to pass on to their successors.

Rudolf Hartmann served as general manager for fifteen years from 1952 to 1967, working side-by-side with general music directors Rudolf Kempe, Ferenc Fricsay and Joseph Keilberth. Two significant events occurred during the Hartmann era: the return to the restored Cuvilliés Theatre with Le nozze di Figaro in 1958 and the reopening of the National Theatre on November 21, 1963. With the aid of the “Friends of the National Theatre” it rose in old classicistic glory like a phoenix from the ashes in accordance the plans of Gerhard Graubner and Karl Fischer.

A new era at the Munich Opera began in 1967 when Günther Rennert assumed the reins. Together with Wolfgang Sawallisch, who functioned as general music director from 1968, Rennert took his comprehensive concept of a well-balanced blend of avant-garde theatre and music theatre and turned it into reality in the form of world theatre with a view toward modernism. His plans also included world-renowned guest artists, including such eminent stage directors as Boleslav Barlog, August Everding, Leopold Lindtberg, Oscar Fritz Schuh, Vaclav Kašlik, Bohumil Herlischka and Jean-Pierre Ponelle. With the 1976 Festival, Günther Rennert took his leave of the Munich Opera.

After an interim year under the leadership of Wolfgang Sawallisch, August Everding became general manager until 1982. His repertoire from Monteverdi to Reimann comprised both traditional operas and contemporary music theatre works. The high point of August Everding’s five-year administration, during which many international opera stars made their first appearances in Munich, was the world première of Aribert Reimann’s Lear in a production by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle, presented on July 9, 1978. In 1983, Everding assumed new responsibilities as General Director of Bavaria’s State Theatres. Wolfgang Sawallisch as State Opera Director, combined the posts of theatre and music director making him artistic director of the Bavarian State Opera.

Wolfgang Sawallisch found it an appealing idea to put the extraordinary options and efficiency of “his” house to the test by presenting large work cycles. In 1983 he offered audiences the unique opportunity of witnessing all 13 of Richard Wagner’s music dramas. In 1988, he opened all of Richard Strauss’s works to discussion in an unprecedented full cycle of the composer’s stage works. In 1987 he brought out a completely new production of Wagner’s Ring during the regular season in the short space of 10 days. At a time when the top productions of the major houses were always interchangeable as far as selection of works and casting were concerned, he sought individual artistic paths. In the ten years of his administration as State Opera Director he tried to stress the unique profile of the Munich Opera, among other things by placing greater weight on dramatic operas and lending special emphasis to classic modern works.

From 1993 until the end of the season 2005/06, Sir Peter Jonas was general manager of the Bavarian State Opera. This Englishman of German descent was previously artistic director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the English National Opera in London. With all respect for tradition, Sir Peter has concentrated more strongly than his predecessors on the theatrical element in opera, including the visual aspect. New stage directors and designers have given the traditional house an innovative, adventurous profile, which was also communicated to the general public through a contemporary approach to PR.

Sir Peter Jonas (knighted in 1999 by Queen Elizabeth in recognition of his services to the Bavarian State Opera) has managed, after a long period of neglect, to restore baroque opera to the repertoire and, in a joint effort with conductor Ivor Bolton and such stage directors as Richard Jones, David Alden and Martin Duncan, he has developed and established a new Munich baroque style. The Festival program has also been expanded: the Prinzregententheater was regained as a performance venue. “Opera for All” appeals to a wide segment of the general public. The cross-over, experimental Festival+ series not only enhances the Festival program but also brings new influences from other art forms into our concept of theatre.

From 1998 until 2006, with Zubin Mehta, another major conductor was guiding the musical destiny of the house, again with great respect for tradition but also with an inquisitive eye toward the future.

Sir Peter Jonas and Zubin Mehta have decided not to extend their contracts beyond 2006. Kent Nagano has assumed his post as Bavarian General Music Director starting with the 2006/2007 season. He also served as interim State Opera Director in collaboration with Dr. Roland Felber, Ronald H. Adler and Dr. Ulrike Hessler until 2007/2008.

Beginning in the 2008/2009 season Nikolaus Bachler has become the general manager of the Bayerische Staatsoper. At the 2013/2014 season Kirill Petrenko has become the Bavarian General Music Director.

Text and pictures courtesy of the Bayerische Staatsoper web site.

I was happy to be engaged at the Staatsoper by Rudolf Hartmann and Wolfgang Sawallish singing many great leading roles including “Prometeus” and “Antigone” , (Kreon) with and composed by the great Carl Orff. And the myriad of brilliant artists associated with the NationalTheater at that time, Carl Orff mentioned me in his autobiography at the time. It was and is thrilling to have been a part of this time in history!

LikeLike

The bombed out theater is NOT Munich, that is the Staatsoper in Berlin!

LikeLike

The “bombed out” theater is NOT the Bayerische Staatsoper, but the Berlin Staatsoper!

LikeLike

Thank you very much Evan fr the correction. I was in the impression that it was the one in Munich, according to the image labeling. I removed the image, since it is not the correct one. Please let me know if there is a proper one of the Munich Staatsoper that I can retrieve. Thanks,

Tiziano Thomas Dossena

LikeLike